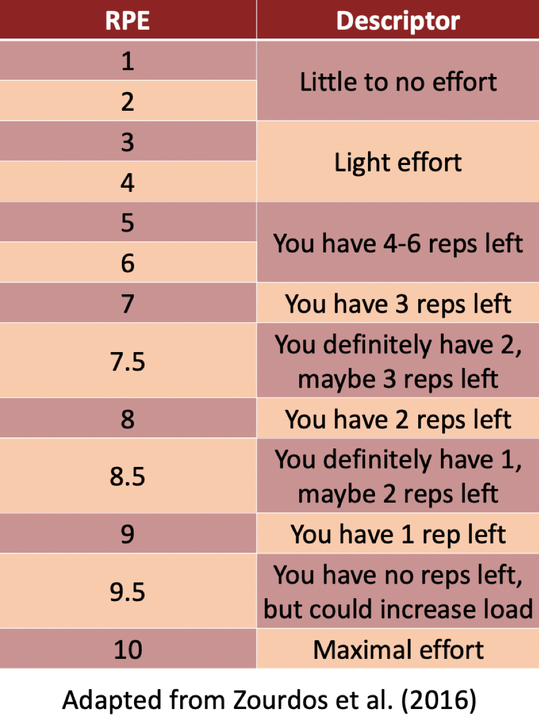

The last three or four reps is what makes the muscle grow. This area of pain divides the champion from someone else who is not a champion. That’s what most people lack, having the guts to go on and just say they’ll go through the pain no matter what happens. To build muscle effectively, you need to train hard. Muscular or technical failure is the epitome of “hard training”, but doing this all the time can have a number of downsides – like an increased injury risk and an inability to recover – that can actually prevent you from maximising your progress. However, it’s easy to tell when you hit failure. On the other hand, it’s not so easy to stop before failure and still train hard enough to stimulate meaningful muscle growth. The reps in reserve-based (RIR) rating of perceived exertion scale (RPE) is an evidence-based tool that helps you do exactly that. I’ve personally applied it in my own and my clients’ training with great success for the past three years. If you want to learn more about what the RPE scale is and how to use it, read on. Why do you need to train hard to build muscle? In 2020, I published an in-depth article to answer this question, and I recently updated it to match my current training and coaching experience, and my understanding of the scientific literature on this topic. You can read the article in full here. In summary, mechanical tension appears to be the primary driver of hypertrophy. The closer to failure you take each set, the higher the amount of mechanical tension each muscle fibre involved generates and senses, the higher the hypertrophic stimulus each fibre receives. In addition, training close to failure ensures that you’re recruiting as many muscle fibres as possible according to Henneman’s size principle, which states that motor units – comprised of a neuron plus all the fibres this neuron “commands” – are recruited from the smallest to the biggest. Finally, you don’t need to achieve muscular failure on every single set to grow muscle effectively. Not only is it not necessary, but it could also be counterproductive to your ability to recover and perform well. Worse performance and recovery would result in less hypertrophy. But if you’re not always training to failure, how do you know you’re training hard enough? Knowing when you’ve reached failure is easy: you try to complete a rep, but either you stop half-way (muscular failure) or your form goes to hell (technical failure). However, if you’re training close to failure, things can get confusing. How do you know when to stop a set and still feel confident that you’re giving your muscles an effective hypertrophic stimulus? My favourite tool to accomplish this, is the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale based on the concept of reps in reserve (RIR). What is RIR? If you’re leaving reps “in reserve”, you’re ending a set before hitting failure. For instance, if you can do a max of 10 reps with 20 kg, but you stop the set after doing 7 reps, you left 3 reps in reserve. What is the RPE scale? It’s a subjective rating system used to describe your exertion during physical work. The original RPE scale, devised by Gunnar Borg, doesn’t work too well in the context of resistance training. The scoring system includes vague terms, such as “light”, “hard”, and “extremely hard”, which don’t necessarily correlate with mechanical tension. For instance, let’s say that you’re doing a set of 40 reps. By the end of the set, you’d probably be in a pool of sweat and cursing your coach, and you’d likely rate this set as “very hard”. However, while your cardiovascular system is certainly working hard, your muscle fibres may or may not be producing enough mechanical tension to get an adequate hypertrophic stimulus. That’s why I employ a different RPE scale, first popularised by Mike Tuscherer, founder of Reactive Training Systems (RTS). This version of the scale is based on your reps in reserve, and requires you to rate each set from 0 (10 reps in reserve) to 10 (no reps in reserve). This is what the RIR-based RPE scale looks like: Since the scale is based on your reps in reserve, it’s a more effective tool than the original RPE scale to gauge whether you’re training hard enough to stimulate hypertrophy.

Based on my understanding of the research that I’m aware of, training within the 7 to 10 RPE range – thus leaving 3 to no reps in reserve – appears to maximise hypertrophy. Circling back to my previous example, if you can do a max of 10 reps with 20 kg, and you perform 10 reps with this weight, you’ll assign this set a rating of 10 on the RPE scale. On the other hand, if you perform 7 reps with the same weight, you’ll assign the set a rating of 7, because you could have done 3 more reps to reach 10, so you left 3 reps in reserve. What does it look and feel like when you’ve reached your last three reps in reserve? As I’ll expand upon in the next subsection, your last three reps before failure – the 7 to 10 RPE range – look and feel a little different depending on the makeup of your muscle fibres – which is unique to you – and on the specific exercise you’re performing. Therefore, you’ll have to practise a multitude of lifts for some time in order to improve your ability to gauge your reps in reserve across all of them. However, in my experience, the following general guidelines can be applied to many, if not all, exercises: 1. Failure is a rep you can’t complete with good form. As a result, you either stop half-way through the rep and have to put the weight down, or you complete the movement, but your form breaks down in the process. 2. The first reps in a set are quick, smooth, and easy, and all look very similar. At this stage, your intensity of effort is usually below 5 (you have more than 5 reps in reserve). 3. The first rep where the weight suddenly feels hard, and you need to slow down to complete the lift with proper form, usually corresponds to RPE 5 (5 reps in reserve) to 7 (3 reps in reserve). After this rep, maintaining control over your technique gets increasingly more difficult. 4. Within 5 to no reps in reserve (RPE 5 to 10), your reps slow down until you can’t move the load any longer. In particular, your concentrics (the part of the rep when you’re lifting the weight) get slower and slower with every rep because your muscle fibres are fatiguing and because, based on the force-velocity relationship, the more force a fibre has to produce, the more slowly it contracts. Fatigue and high force production will both contribute to increased mechanical tension, which means more gains! Importantly, you can’t slow your reps down on purpose. For the set to stimulate growth, the decrease in speed needs to happen naturally. In fact, you’re still trying to lift the load as explosively as you can. However, “as explosively as you can” is very slow when you’re very close to failure. The bottom line is that, leaving reps in reserve may not be all-out failure, but it’s still bloody hard. If your workouts are a walk in the park… you need to push yourself harder. How can you make the most of the RPE scale? Like all training tools, the RPE scale isn’t perfect. Its greatest limitation is probably its subjectivity. Specifically, research seems to show that most lifters tend to underestimate the number of reps they have in reserve and thus overestimate their RPE. This means that they tend to train further from failure than they think, which can result in a smaller hypertrophic stimulus than desired. For example, if a lifter rates a set as RPE 7 (3 reps in reserve), they may have four, five, or even six reps in reserve instead. However, research has also demonstrated that you can improve the accuracy of your gauge of reps in reserve. Accuracy seems to increase under the following circumstances:

With these considerations in mind, you can use the following suggestions to boost your own accuracy: 1. Practise different exercises. As I mentioned earlier in the article, the last five reps before failure can look and feel like a different experience depending on the specific lift you’re performing. For instance, when I’m doing a pressing exercise like the bench or shoulder press, I can knock out relatively smooth-looking reps until I hit RPE 8 (2 reps in reserve). The last two reps usually seem to grind almost to a halt, and I have to fight for every additional inch. On the other hand, when I’m leg pressing, I tend to hit a similar “wall” when I’m as far as 5 reps from failure (RPE 5), so I’m more likely to underestimate my reps in reserve. For example, I might think I’ve already hit RPE 8, when in fact I still have three or four reps in reserve. Therefore, to get better at gauging reps in reserve across the board, apply the RPE scale to a variety of exercises. In addition, keep practising the same lift for months at a time to continue honing this skill. 2. Train to failure on occasion, particularly as a less experienced lifter. While training to failure may not be necessary to maximise your gains, you won’t be able to accurately gauge your reps in reserve if you’ve never experienced actual failure. It’d be like asking someone who’s never watched or read Naruto how heart-wrenching Haku’s death was from 0 to 10. They just wouldn’t understand. However, you need to have mastered proper form to train to failure safely, which may not be the case if you haven’t been lifting for very long. So, if you do choose to take a set to failure, pick exercises that are relatively safe and easy to learn, such as single-joint and machine lifts, like barbell bicep curls or machine chest presses. 3. Train closer to failure when doing more than 10 reps on relatively safe lifts. Since your ability to gauge your reps in reserve accurately decreases when you’re doing higher-rep sets, I tend to account for this limitation by programming higher RPE targets (8 to 10) for sets of over 15 reps, and lower RPE targets (6 to 9) for sets of 10 reps or less. Moreover, some exercises are more suited to lighter weights and higher rep ranges, and vice versa. This also plays into my decision-making process. Lastly, some lifts are more technically and physically demanding than others, so taking them closer to failure can take a large toll on your recovery. You can only get results if you can recover from your sessions, therefore I tend to assign lower RPE targets – or to assign higher RPE targets less frequently – to more taxing exercises. For instance, I usually program sets of 15 reps or more, and RPE targets of 9 or 10 – or even failure – for machine and single-joint lifts, which, as mentioned, are also safer and less fatiguing. On the other hand, with multi-joint and free-weight exercises, like barbell squats and deadlifts – which are relatively riskier and more taxing for your recovery capabilities – I tend to program sets of 10 reps or less, and lower RPE targets of 7 to 9. 4. Film your sets. As described earlier, as you approach failure, each rep is going to get slower and slower. You can feel yourself slowing down, but it’s common to overestimate your own decrease in speed unless you can see the set from the outside. That’s why I encourage my clients to film their sets and re-evaluate their rating of perceived exertion after studying the footage. For example, you may feel like you ended a set at RPE 8, then watch it back and realise it was only RPE 7. This has happened to me with many a set of goddamn leg presses… My clients can also submit their videos to me in order to get my own opinion on their reps in reserve and RPE rating. If you have a coach, their feedback can be very useful, since they’ll likely have watched dozens of people training within close proximity to failure. 5. Remember that most people overestimate their proximity to failure. For this reason, whenever you think you’ve hit your RPE target, challenge yourself to do one more rep, especially if you’re still relatively new to using the RPE scale. As I like to tell my clients, you’re usually stronger than you think you are. Practical Takeaways

Thanks for reading. May you make the best gains. To receive helpful fitness information like this on a regular basis, you can sign up for my newsletter by clicking here. To learn how to develop an effective mindset for long-term fat loss success, you can sign up for my free email course, No Quit Kit, by clicking here. To listen to my podcast, click here.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Nikias TomasielloWelcome to my blog. I’m an online fitness coach with a passion for bodybuilding, fantasy, and bread. Want to work with me? Check out my services!Archives

May 2024

Tags

All

|

Follow me on social media |

Get in touch |

© 2018-2023 Veronica Tomasiello, known as Nikias Tomasiello – All rights reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed