Each person’s workout is really different. It’s tailored to be what’s most needed for them. Everybody’s different. If you want to build as much muscle as you can, doing a list of random exercises for 3 sets of 12 reps each just won’t cut it, unless you’re a true beginner. What you need is an effective muscle-building program. The components of any good program are called training variables, which can be structured together in a variety of ways, depending on your fitness level, goals, and needs. In this article, we’ll focus on three of the most important variables for muscle growth:

We’ll cover what they are, what the current scientific literature can tell us about them in relation to muscle growth, and how to implement them in your own program. Ready for the brain gains? 1. Volume The volume of work allocated to each muscle in your training program appears to be one of the most important contributors to muscle growth. If you aren’t familiar with this term, I gave a longer definition of volume in this article about the differences between training for strength and training for muscle size. In the current article, when using the term “volume”, I’m referring to the number of hard sets performed for every muscle or body part per week. So, how much volume do you need to make gains? The answer to this question isn’t straight-forward. Your volume requirements can vary depending on:

All these factors but the first one are bound to evolve over time, so your volume requirements are also likely going to change. Therefore, the volume that you personally need to grow more size can’t be found by reading a blog article, but only by training and experimenting until you find what works for you. Nevertheless, hypertrophy researchers have been able to give some general guidelines on volume, based on the studies conducted over the last decade or so, which you can use as a starting point. First of all, effective volume isn’t a single number of sets, but rather a spectrum, from the minimum effective dose to the maximum you can do before overshooting your recovery capabilities. Let’s start with the minimum effective training dose, or the bare minimum volume you can get results from. According to a recent narrative review published in June 2021, “although a high training volume appears superior to maximize muscular adaptations, it is possible to improve both strength and hypertrophy when training with a relatively low number of weekly sets (< 5 sets)”. The paper recommends a minimum of four sets per week for two reasons:

So, as far as we know at the moment, as little as four sets of a single exercise for each muscle group could elicit some improvements in muscle size. If you can’t train for more than two or three days per week, this is great news! But what if you wanted to make as many gains as you possibly could? A paper from 2018 suggests to aim for weekly volumes of 10 to 20 sets per muscle group in order to maximise gains in muscle size. Now, if a higher training volume seems to yield more muscle growth, surely more will be better, right? That’s what I thought at the start of my lifting career. At the time, I was doing 20 or more sets per muscle per week. However, after years of training myself and others as an online coach, I found that this “more is better” mindset usually results in doing a lot of so-called “junk volume”, or extra volume that causes more fatigue than gains. Too much fatigue can compromise your progress overall, so this extra volume doesn’t benefit you at all and can in fact even hold you back. Therefore, instead of jumping straight to 20 sets, like I did, start with the lower end of these guidelines, and only increase your volume if and when needed to continue improving your physique. In summary, you can increase your muscle mass with anywhere from 4 to 20 sets per muscle group per week. Although higher volumes may be useful to optimise muscle growth, you can make some progress with a lot less. 2. Intensity of load Intensity of load is the amount of resistance provided by an exercise, or how much weight you’re lifting. The load can be internal, like when you’re lifting your own body in a push-up or pull-up, or external, like a dumbbell or a resistance band. A common way to express intensity of load is to use a percentage of 1 Repetition Maximum (1RM), which is the maximum amount of weight you can lift with good form for a single rep. For example, if you can lift 100 kg for one rep, but not two, 100 kg is 100% of your 1RM, 40 kg is 40%, 63 kg is 63%, and so on. Based on the current scientific literature, it seems like you need to lift at least 30% of your 1RM in order to increase muscle mass. However, testing your 1RM for every exercise in your program isn’t always practical or safe, so you can also express intensity of load as a certain number of reps to failure. For instance, if you can lift 20 kg for 30 reps but not 31, 20 kg is your 30RM (30 Repetition Maximum). This 2015 study appears to show that you can gain muscle with loads that are as heavy as your 8 to 12RM, or as light as your 25 to 35RM. In addition, this meta-analysis suggests that, when training to or close to failure, you can perform 6 to 20 reps and experience muscle growth. So, if you’re taking a set to or close to failure, you can see results with both relatively heavy (6 to 12 reps) and relatively light loads (25 to 35 reps). In other words, you can make gains even if you don’t have a lot of weight available and you need to do a lot of reps per set (pandemic home gym, anyone?), as long as each of those sets is hard enough. 3. Intensity of effort Intensity of effort is a subjective rating of how hard each set feels. The maximum intensity of effort you can experience in a set is called failure, which can be divided into three categories:

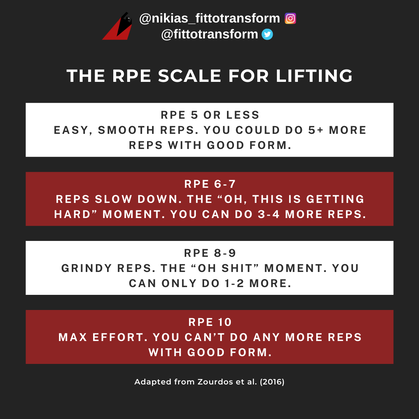

I posted a visual representation of these three definitions of failure here. If you’re familiar with the lifting culture of “No pain, no gain”, you might assume that you need to train to failure all the time in order to build muscle… But do you? According to a 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis, this may not be necessary, as long as you’re performing enough volume. At the same time, if that’s your preference, training to failure doesn’t seem to be detrimental, either, as long as it doesn’t affect your recovery. Another consideration to make is that, if you train to failure all the time, you may need to reduce your training volume in order to safeguard recovery. Given that volume appears to be a very significant driver of muscle growth, whereas you can get similar benefits to hitting failure by keeping 1 or 2 reps in reserve, this may not be a worthwhile trade-off if your goal is to optimise your muscular gains. Instead, it might be more productive to be able to do more volume and recover from it by training with at least 1 or 2 reps in reserve. If you want to read more of my thoughts on the topic, I wrote a whole article on training to failure here. However, aiming for failure makes training easy: you stop when you can’t complete another rep. If you aren’t going to failure, when do you end a set? A popular way of expressing intensity of effort makes use of the RPE scale (Rating of Perceived Exertion), based on RIR (Reps in Reserve), or how many reps with good form you believe you can do before hitting failure. For visual examples of what the RPE scale looks like in practice, check out some of the posts and videos I created on this topic in my Instagram guide to resistance training. This is what the scale looks like: In a 2016 paper exploring the potential applications of the RPE scale to strength and muscle gains, the researchers recommend to perform each set to a RPE of 8 to 10, depending on what would be most appropriate for your current training phase.

A more recent meta-analysis investigating the use of sets as a proxy for volume for muscle hypertrophy, recommends to leave only 3 or fewer repetitions “in reserve”, which would correspond to a RPE of 7 to 10. For example, if you can lift 50 kg for a maximum of 10 reps, you’d achieve a RPE of 7 with 7 reps, a RPE of 8 with 8 reps, a RPE of 9 with 9 reps, and a RPE of 10 with 10 reps. If you attempted the 11th rep, you wouldn’t be able to complete it. To recap, you may not need to take every set you do to failure, but you may still want to make each set challenging by aiming for a RPE of 7 to 10 (3 to zero reps in reserve). Bringing it all together Volume is an important contributor to muscle growth, and can be measured using the number of sets per body part or muscle group that you perform every week. The current general guidelines recommend a minimum effective dose of 4 sets and up to 10 to 20 sets per week in order to optimise growth. However, not all volume is created equal. If you want your sets to help you grow more muscle, you need each one to tick these boxes:

Practical takeaways

To receive helpful fitness information like this on a regular basis, you can sign up for my newsletter by clicking here.

2 Comments

1/17/2022 12:53:37 pm

What an exquisite article! Your post is very helpful right now. Thank you for sharing this informative one.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Nikias TomasielloWelcome to my blog. I’m an online fitness coach with a passion for bodybuilding, fantasy, and bread. Want to work with me? Check out my services!Archives

May 2024

Tags

All

|

Follow me on social media |

Get in touch |

© 2018-2023 Veronica Tomasiello, known as Nikias Tomasiello – All rights reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed